Returns: The J-Curve and IRR

Manager Selection and Capital Allocation

How are private equity returns measured and why? What does this mean for investors allocating to private equity?

Part 1 of 3 of this series on returns looks at the J-curve and IRR:

Investing in a private equity fund is to invest in a series of long-term cashflows;

the nature of private equity cashflows leads to the ‘J-curve’;

investors that misunderstand the J-curve often under-allocate to private equity; and

IRR is a useful metric to measure performance provided the practitioner understands what it measures, the J-curve and incentives.

Cashflows

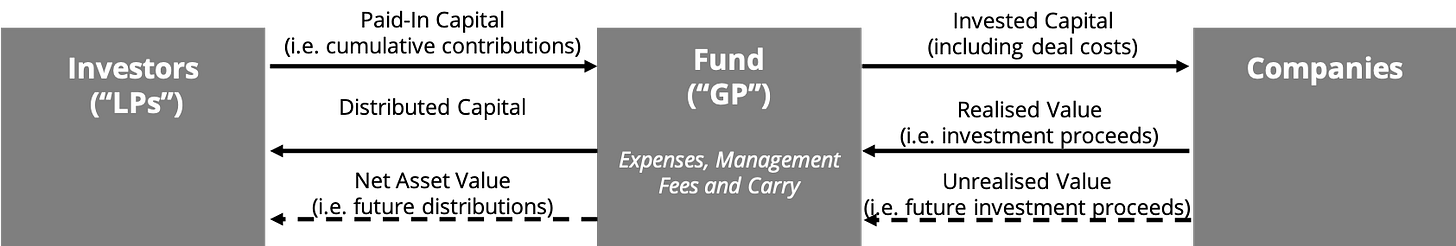

To invest in a private equity fund is to invest in a series of cashflows. Cash outflows are ‘drawdowns’ (or ‘capital calls’ or ‘contributed capital’); private equity funds request these amounts from investors in the form of a ‘drawdown notice’ or ‘capital call notice’. Sometimes, the term ‘Paid-in Capital’ is used to represent the cumulative cash outflows to date. The amount and timing of these cash outflows are uncertain because they fund investments in underlying companies, which are yet to be sourced, negotiated and closed. All we know is there will be more contributions than distributions in the early life of a fund.

Cash outflows are ‘distributions’ to investors after realising an underlying investment in a company (e.g. proceeds from a sale or IPO). Again, the amount and timing of these cash inflows are uncertain because they come from realisations yet to be marketed, negotiated and closed. All we know is that, notwithstanding a catastrophe, there will be more distributions than contributions in later years.

Through time, contributions decrease as fewer investments are made and distributions increase as more investments are realised. The net cash position will turn from negative to positive. The chart below illustrates the contributions from investors in orange and the distributions to investors in blue. The grey line is net cash position.

Internal Rate of Return

The most important question in assessing fund performance is clear: did the GP do a good job? It’s a simple question but answering it is anything but. - Howard Marks

To value this series of cashflows, the internal rate of return (“IRR”) can be used. Many investors, particularly those experienced in public equities, are drawn to IRR over multiple-based metrics because IRR looks like an annual return percentage.

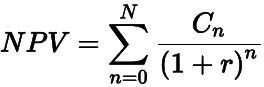

However, IRR is not an annual return. It’s the discount rate that makes the net present value of all cashflows equal to zero (or the rate that makes the present value of cash outflows equal the present value of cash inflows). IRR is not the measure of wealth that some investors may think it is. So why use it? An example adapted Oaktree’s Howard Marks illustrates why annual returns don’t work in private equity:

Investors contribute $10 to the fund for it to make investments in underlying companies. In year 1, the fund’s portfolio gains $2, which is an annual return of 20% on the $10. The fund also achieves some liquidity in year 1 (e.g. from a partial sale of a company) and distributes $6 to investors. The fund is valued at $10, plus the $2 gain less the $6 distribution (=$6). In year 2 second, the fund’s portfolio gains $1.50, which is 25% on $6 of capital. The fund also distributes a further $7 to investors. In year 3 we have a gain of $1 on only $0.50 of capital or a 200% annual return.

The 200% gain is on $0.50 of capital, but only creates $1 of wealth. The seemingly smaller 20% gain is on $10 of capital, creating $2 of wealth. A total annualised return of 65% p.a. is a misleading indicator of overall performance because some returns are on smaller amounts of capital than others. On the other hand, IRR weights returns on more capital higher, and returns on less capital lower.

Calculating IRR and the J-curve

The IRR for a fund is calculated from the very first cashflow to the present time. An example reference to IRR might be “IRR from inception to June 2020” or simply “as at June 2020.” IRR is calculated by solving for the rate of return (“r”) of a series of cashflows (“C”) over a period of time (“n” to the total number of periods “N”):

Luckily, excel has an XIRR function, which lets you input the cashflow amounts against the cashflow dates. (The XIRR function has an optional field, which is your best guess for r. A guess is sometimes needed, usually if IRR is a negative number, because the equation above has more than one solution.)

Here is an illustrative IRR over time for our PE cashflows:

We can see that, similar to the net cash flow position, IRR is a J-shaped curve. Early in the fund, three things are happening: 1) there are more contributions than distributions; 2) fees are charged on committed capital while returns are earned only on capital contributed for investment; and 3) those investments are initially held at cost until there’s a catalyst for (hopefully) increasing the valuation. This provides a negative net cash position and IRR, before the inverse becomes true. The ‘J-curve’ is simply a general way to represent this.

Not knowing what drives J-curve (being the three points above) is the most common reason investors under-allocate to private equity. If an investor commits $10m, that $10m won’t be put to work immediately but contributed over time. In fact, just as contributions are highest, investors will start receiving distributions; the capital ‘in the ground’ at any one time will never reach $10m and misunderstanding this leads investors to invest far less than they intended.

Two final points related to IRR over time:

An IRR calculation is less sensitive to later cashflows, which are towards the end of a fund’s life. As we see above, the rate of change in IRR decreases over time.

An IRR calculation becomes more meaningful as the fund matures. Using our hypothetical cashflows, if we found ourselves in year 4, our IRR would be -20% p.a. In year 12, it is above 20% p.a.

The above is why an IRR number by itself has little value. The vintage of the fund should be read alongside an IRR. The vintage is the date the series of cashflows began. More specifically, the vintage is the year the fund made its first investment (although some practitioners define it as the year the fund was “formed”). We then know where we are along the J-curve and so can put IRR in context.

(An IRR of -10% for a 2018 vintage fund is nothing to be worried about – we expect net cashflows to be low or even negative for the first few years. The same IRR for a 2010 vintage fund is a worry– by then we’d certainly expect net cashflows to be positive. For this reason, I would suggest ignoring IRRs for vintages less than 4-5 years old. IRR becomes more meaningful with the passage of time).

IRR in Practice

IRR is a useful performance measure, provided the practitioner understands: 1) the J-curve; and 2) the IRRs for comparable funds based on vintage, strategy and geography.

On this latter point, it is best to think of IRR as a yardstick to measure the performance of one fund against others or a benchmark. I think of it as setting a baseline from which to measure relative performance. A CFO would use IRR to compare the profitability of a set of possible capital projects; private equity investors should use it similarly (a difference being a CFO would estimate IRR based on future or ex-ante cashflows, whereas private equity investors use historical or ex-post cashflows).

Finally, two ways private equity funds (more specifically, their managers) can distort IRR:

The importance placed on IRR by investors incentivises PE funds (i.e their managers) to strategically time cashflows. For example, if $50 is invested into a company that can either be: a) exited in year 2 for $75; or b) held for two more years for a further $25 gain, the PE fund may choose the earlier exit for a better IRR, despite generating more wealth by exiting later.

Exiting earlier also means investors need to re-allocate those proceeds in year 2, even though they may prefer to leave the cash in for a few years (an investment hurdle rate of 19% p.a. is a high bar and tough to get right consistently).

Regardless of whether this is done in practice, the incentive is there, so investors should be aware of it.

IRR can be ‘levered’ using subscription lines. Subscription lines are a loan from a bank to the PE fund, secured against that fund’s investor commitments. The PE fund can then use the bank’s money to invest in companies or pay expenses, rather than call capital from investors. Eventually, the fund will need to call capital from investors (to settle the subscription line and fund the remaining investments and expenses) but this can be done later. Using the same example above, the PE fund now uses a $50 subscription line to invest in the company then calls capital at the end of year one (instead of year 0):

Evidently, delaying cash outflows provides for a far better IRR. It is important to note that using subscription lines ‘levers’ IRR and not absolute returns or capital to invest (i.e. they cannot be used to borrow more than the committed capital). See Howard Mark’s excellent letter for more on this.

Conclusion

IRR has criticisms, including the two problems highlighted above. However, I think blanket criticism that attempts to invalidate its use entirely misses the point. There are always trade-offs using one tool over another and no metric should be used in isolation. Numbers are abstract and have no meaning except for the meaning we decide to attach to them.

In the case of IRR, it is most useful as a yardstick to compare relative performance between funds or against benchmarks, provided the practitioner understands the J-curve (i.e. cashflows and time) and the incentives. Investors should always be thinking about the latter anyway; understanding incentives is table stakes in private equity.

Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome. Never, ever, think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives. - Charile Munger