Join investors, institutional allocators, family offices and those who want an edge in private equity by subscribing to Letter Capital here:

Provided the investor allocates to the right managers, private equity can provide an ‘equity risk premium’ plus some outperformance over the public market. If that outperformance is more than any incremental risk (e.g. illiquidity, leverage), then we push past the efficient frontier towards ‘alpha.’ The true alpha is the return attributed to the fund manager’s skill rather than other factors such as small-cap bias, sector weighting or manager-owner alignment that can be inherent to private equity.

True alpha is the measure of return related to skill, which can be repeated and therefor, is the persistent return.

Persistence is the keyword. A dollar invested will generate returns in the future, but we only have historical returns as a basis for making investment decisions.

Many in the industry use the term alpha to mean any outperformance over the public market or peers. Private equity managers will claim this outperformance but how much of it is attributed to skill and how much to other factors, including luck? If a manager is, for example, outperforming the public market because it is able to buy a company with more debt than typically used in public companies and then exploit a longer-term investment horizon to maximise total return (rather than quarterly earnings), is that skill or a point of parity common to the asset class? I argue it’s the latter.

Skill can be repeated. Luck cannot. Skill is the only factor in private equity outperformance that is persistent.

Alpha as I define it, is the “competitive advantage” concept in business applied to private equity. The rest is competitive parity. If an allocator cannot identify alpha, then that manager does not have an edge.

Returns based on skill are available in private equity because it is an inefficient market. Inefficient markets lead to a wide dispersion of under and overperformance outcomes.

Measuring Outperformance

So how does one measure this outperformance? When given a track record by a manager, with lots of IRRs and multiples, how do you know if: (a) that track record has outperformed; and then (b) any outperformance is likely to persist in future (i.e. the alpha or skill, excluding other factors in PE)?

To determine (a) we use a tool to quantify the total outperformance: Public Market Equivalent (“PME”). It calculates the annualised return in excess of a specific public market index. We use PME as a heuristic to strip out the risk-free rate and equity-premium common to all equities, by using a public market index as a proxy. What is left is the total outperformance, including true alpha, luck, leverage etc.

There are a number of PME calculation methods, all with the same premise:

capital contributions to the PE fund from investors are instead, invested in the specified public market index at that time; and

distributions from the PE fund to investors are instead, a sale of the public market index at that time.

Remember, the returns we have from the PE fund are all ex-post, that is, after the fact. So, we calculate the above in the same way. We calculate the future value of each cash flow (contributions and distributions) as if it was invested in the public market index.

Direct Alpha is the best PME method because it is simple and intuitive. We don’t go into the pros and cons of each method here; see the Gredi, Griffiths, Stucke paper for a comparison between Direct Alpha and the other methods.

Confusingly, the name Direct Alpha is a misnomer. It calculates (a) above, in other words, the total outperformance, which includes outperformance both relating to (true) alpha or skill, and also other factors (luck, better governance inherent to the asset class etc). To restate the formula above using Direct Alpha:

Direct Alpha

Direct Alpha is not absolute performance, rather it is performance relative to a public market index chosen by the practitioner. It can be positive or negative. It is negative when the investor was better off allocating to that public market index than the fund (because the index returned more than the fund).

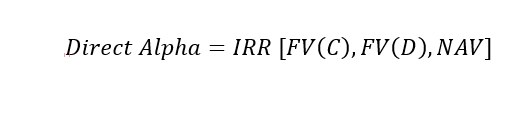

This is the formula for Direct Alpha:

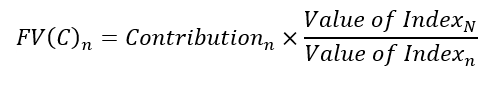

First, we calculate the future value of each contribution (“C”) and each distribution (“D”) as if it were invested in the designated public market index. For example, the future value of a contribution (C) would be:

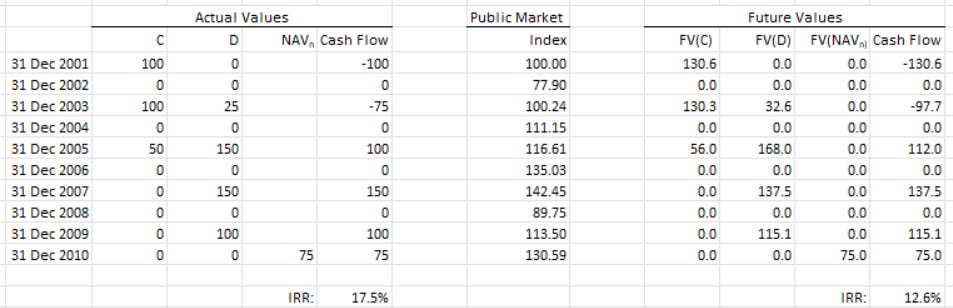

We then calculate the IRR for this series of future values, including the current Net Asset Value (“NAV”). Here is the example from the Gredi, Griffiths, Stucke paper:

This example says the Direct Alpha, or excess return over the index, is an IRR of 12.6% p.a. The total outperformance is 12.6% according to the Direct Alpha method.

The market-related return is the difference between the actual IRR and the Direct Alpha (17.5% - 12.6% = 4.9%). In other words, the Direct Alpha calculation implies that the public market returned 4.9%.

If you’d like the example calculation in Excel, email lettercapital@substack.com or DM me on Twitter @michael_sterry

The choice of index is up to the practitioner. The most common indices used are the MSCI World, Nasdaq or S&P indices or any local or industry-specific industries that provide a relevant benchmark for that particular PE fund. We want to use the total return for these indices, not just the price (we’re comparing apples to apples - total returns of the PE fund with total returns in the public market, including dividends.)

(True) Alpha

We have now calculated the total outperformance (Direct Alpha). We’ve answered (a), the first question: “has the fund outperformed and by how much?”.

That’s history though and our investment now will generate returns in the future. We need to answer (b), the second question: “how much of this historical outperformance is persistent?”

Determining this definitively is impossible but we can form a view by understanding how much of the total outperformance is related to skill (hence is alpha), and therefore a fighting chance to persist in the future (assuming the same team, strategy, process, etc). We strip out any other factors and we’re left with Alpha:

Or using the example above:

What are these other factors? They include, as alluded to above:

sector weighting (which you may decide is captured already if a sector-focused public index is used for the Direct Alpha);

small-cap bias (again, which may also be captured if a small-cap index is used);

leverage;

inherent ‘owner-orientation’ to resolve some of the agency problems between management and owners in business; and finally

luck, which is very hard to unpick but must be accounted for, however imprecise or esoteric.

There are methods we can use to estimate both True Alpha and Skill, and the Other Factors, which we will go into in another article. For now, we have a framework for understanding outperformance in PE.

As a quick aside, arguably, success in private equity almost always begins with luck. Luck begets skill. For example, it can be argued that all successful venture capital managers were lucky early, with a couple of extreme outcomes, which allowed them to raise more capital and develop skill, which is persistent.

“Every science begins as philosophy and ends as art: It arises in hypothesis and flows into achievement.” - Will Durant

The Hardest Job

As I wrote in Alpha Allocators, inefficiencies in private equity allow for returns based on skill. Skill varies. It could be unique sourcing ability, due diligence that others cannot do, or some genuine operational advantage the manager can bring to the table. Sometimes, it is as simple as the manager installing the very best operator in that industry (read Railroader for the brilliant pairing of Bill Ackman as the manager and Hunter Harrison as the operator).

Only skill can exploit an inefficient market to generate persistent outperformance over time. And a track record is useless if it doesn’t inform a view of the future.

It is the allocator’s job to work out which, and to what degree, each of skill, luck and other factors contribute to the outperformance of any one manager. This is part art and part science, based on quantitative analysis that is useless without the qualitative context (e.g. a long relationship with that manager).

One allocator’s view of the returns generated by true alpha will differ from another; one allocator might think a first-time manager got lucky, whereas another might think the partners have a special skill in consumer businesses, deep-tech, turnarounds or whatever. One allocator might have a high conviction necessity of the luck→skill path dependence in private equity, and therefore is more willing to invest in emerging managers without tenured track records.

New CIO role? The toughest task for the first year or so will be getting access to the top-performing funds. This may never happen. If it does, then you have an even tougher task: how do I know which of these outperforming funds will persist, using the returns based on skill, or true alpha, as a proxy? This may never be answered or inevitably, the allocator comes up with the wrong answer.

An allocator might meet a new manager over a coffee, beer, or in their office, typing lots of notes, trying to get a feel for them as a person or “eyeballing them”. They may do this several times until they feel “comfortable”. We think we’re a better judge of a person’s character, humility or honesty than we are, particularly if it is a new manager relationship. This leads to false precision at best and the wrong answer at worst. We might believe, for example, that there are mitigating factors that make the prior track record worse than what it “should be” given what we “feel” about that manager after meeting them. Then, of course, sometimes there are mitigating factors that the best allocators can spot and account for.

“We think we can easily see into the hearts of others based on the flimsiest of clues. We jump at the chance to judge strangers. We would never do that to ourselves, of course. We are nuanced and complex and enigmatic. But the stranger is easy.” - Malcolm Gladwell

This is why I believe, that unless you are allocating to a manager based on years of seeing them do what they said they would do, an allocator will need to accept two things: (1) there is risk in investing in managers that cannot be mitigated or explained away; and (2) when making allocation decisions, forming new relationships will pay off in the long-term (e.g. the subsequent funds), but in the short-term, may do more harm than good.

Many private equity allocators eventually accept returns that are the same as a passive public market index, despite more work and sometimes, more risk. They just feel better about those returns because they have done plenty of busy work or have had a beer or enjoyable chat with the particular managers they chose to invest in.

The few allocators that have turned their allocation from philosophy, into science, and eventually art, are the few that generate outstanding outperformance over many years.